On this Saturday, students across the United States are asking you to join them in a national day of actions at outlets of REI, a sporting goods chain. In places like Rockville, Maryland (see below) or Seattle, Washington, they will be asking REI to do its part to support worker safety in Bangladesh.

In order to understand why students are protesting REI, we need to follow the money from Rockville and Seattle to Dhaka and Narayanganj in Bangladesh.

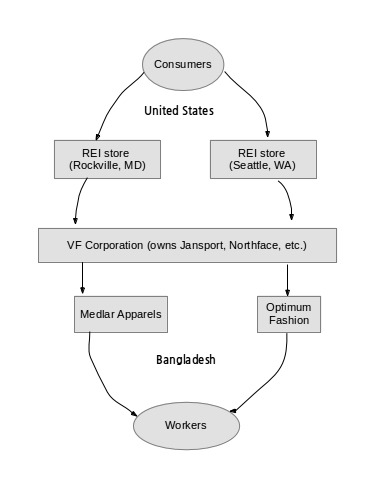

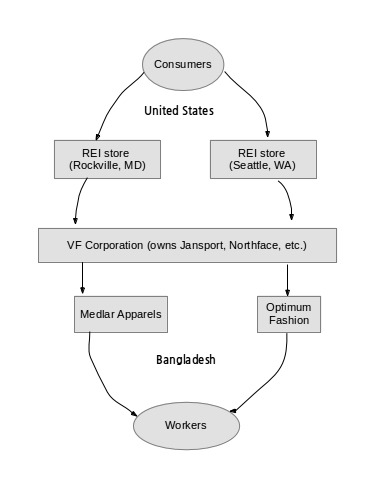

The graphic above shows the path of the cash which leaves the consumers’ hand for the registers of REI. REI, in turn, pays Greensboro-NC-based VF Corporation for the backpacks, pants, sleeping bags, and other goods it stocks. VF Corporation, in turn, has contracted out the work to produce its goods to factories in Bangladesh like Medlar Apparels and Optimum Fashion (pdf). Finally, these factories have pushed their workers, for extremely low pay and long hours, to produce the goods on time and with sufficient quality; in exchange the workers receive a very small percentage of the total cost the consumer paid.

Bangladesh’s garment industry is experiencing a crisis in terms of building safety and other, very basic measures of worker well being. This crisis was concretized in the collapse of Rana Plaza, a multistory building where over 1,100 workers died in April 2013.

There are two main efforts right now to try to establish basic conditions like ‘the building won’t burn down’ in Bangladesh’s garment sector. The first is the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety, which, according to USAS, is a legally binding agreement between brands and legitimate representatives of workers in Bangladesh. Importantly, the Accord includes unionizing and other worker organizing into the basic framework for improving building safety; as such, it recognizes that worker organizing is important not just in and of itself, but also vital for ensuring that worker concerns about building safety are heard.

The alternative to the Accord is a company sponsored effort called the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety. The Alliance is an initiative spearheaded primarily by American corporations like Wal-Mart and lacks the teeth that the Accord has. Most importantly, it does not have the same practical commitment to the importance of worker organizing.

Back to this Saturday. What USAS is asking consumers–asking you to do –is to use the leverage that you have over REI by requesting that REI remove VF Corporation’s goods from its shelves. If successful, this would put further pressure on VF Corporation to sign up to the stronger measure, the Accord, and thus lend support to active worker organizing efforts in Bangladesh by legitimate representatives.

It may sound complicated, but it boils down to a very simple fact: in that diagram above, the consumers are the only group of people besides the workers themselves that can be reliably asked to take the side of labor. If you can, show up at an REI near you to support Bangladeshi workers on Saturday. Here’s the announcement for the DC area action:

Take Action at REI in Rockville, MD to End Deathtrap Working Conditions in Bangladesh

Who: United Students Against Sweatshops, the nation’s largest student-run organization supporting workers rights, and YOU!

What: Since 2005, more than 1,800 garment workers have died in preventable factory fires and building collapses in Bangladesh. In the wake of these disasters and in the face of massive pressure from consumers, over 175 apparel brands have signed the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, a legally-binding agreement between brands and unions that holds the promise of bringing an end to mass fatality disasters in the garment industry.

Unfortunately, North Face its parent company, VF Corporation, have refused to sign this groundbreaking agreement. Instead, the company has teamed up with its buddies from Walmart to create a fake safety program that excludes workers and is not legally binding.

Students and consumers are taking action at REI stores to demand that the company pull all North Face products from its shelves unless VF signs the Accord. Unfortunately, just this month REI said that it would not cut ties with North Face or meet with students to discuss the company’s human rights abuses. Now we’re stepping up the pressure to show REI that our demands can’t be ignored.

When: 12:30pm, Saturday, July 26th

Where: 1701 Rockville Pike, Rockville, MD 20852