The continuing aftermath of a disaster

As health and safety concerns around workplaces have reentered American public dialogue, it is worth noting that yesterday marked the seventh anniversary of the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh. Over 1,000 people died in the worst industrial disaster in the history of the garment industry.

Last August, I wrote a piece for Labor Notes on the state of efforts to prevent a similar disaster from happening again:

On April 23, 2013, a local television crew shot footage of cracks in the Rana Plaza factory complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The building was evacuated, but the owner of the building declared it safe and told workers to come back the next day. One Walmart supplier housed in the building, Ether Tex, threatened to withhold a month’s wages from any workers who didn’t return.

The building collapsed on April 24, and when the rubble was finally cleared, 1,134 people were found dead, with another 2,500 injured. It was the worst industrial disaster in the history of the garment industry.

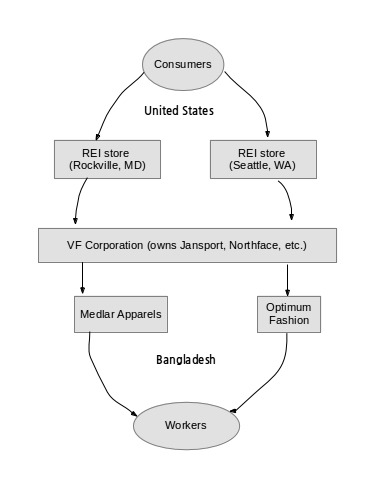

From the ashes of Rana Plaza emerged the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety. An international compact among nonprofit organizations, Western manufacturers and retailers, local Bangladeshi union federations, and several major global unions, the Accord has monitored fire and building safety in 1,700 factories in Bangladesh over the past six years for signatory brands.

The upshot of the story was that the Accord, while providing important gains in safety for Bangladesh’s enormous garment sector, did not go all the way in protecting the more fundamental right to organize from which real security on the job stems:

Chaumtoli Huq, a professor at the City University of New York School of Law and maker of the 2017 film Sramik Awaaz (Worker Voices) on the Bangladeshi garment industry, said that’s a problem..“The workers I interviewed in my documentary were very clear in what they think needs to happen—it wasn’t renew the Accord, it was put a union in my factory.” She argues that the international solidarity movement is not sufficiently listening to those workers…

“What’s odd is that you have almost these two parallel movements—you have the Accord piece and you have the wages and unionization piece,” said Huq.

At the time, minimum wage in the Bangladeshi garment sector was about $95 a month, or a quarter of what would constitute a living wage.

What’s changed in the last year? Well, wages sure haven’t gone up.

Instead, a different kind of industrial disaster has occurred. With the pandemic collapsing demand and supply chains around the world by March, one million garment workers in Bangladesh were laid off or furloughed, a quarter of the total workforce in the country’s garment industry. Most were sent home without severance or owed money, according to the New York Times. Most Western brands are avoiding financial responsibility to the workers.

The Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA)’s members, who own not just factories but Parliament itself, are getting bailed out by the government to the tune of $590 million. Workers, on the other hand, have to face the twin calamities of extreme financial distress and worries about the spread of the virus.

The situation shows that responding to Rana Plaza with technocratic fixes and deals with the brands that were narrowly oriented on preventing another Rana Plaza-style industrial disaster—however well intentioned—was not enough. What’s needed to prevent the wide range of catastrophes that can affect workers in the global South is to emphasize building real worker power that can allow Bangladeshi people to advocate for themselves.

Otherwise, all you’ll end up with is another catastrophe down the line—one that is different in nature, but all too familiar in its decimation of the lives of the most vulnerable members of the supply chains that provide goods and services for Western corporations.

It’s not hopeless; it just takes respect for the will and the organizing capacity that Bangladeshi workers themselves already have. Solidarity, siblings.